The Legend of Lizard Man: Horror in Rural Carolina

Liesel Hamilton

It was late—past midnight—on June 29, 1988. Christopher Davis, a seventeen-year-old black teenager, was driving home from his shift at a fastfood restaurant near Bishopville, South Carolina when his ‘76 Celica blew a flat tire and he pulled over to the side of the road. To his left, just off the asphalt, lay Scape Ore Swamp—a low lying wetland typical of South Carolina where the knobby knees and wide buttresses of cypress trees emerge from swatches of low-growing bamboo and pools of slow-moving blackwater, stained dark from tanins.

There was not a soul around, yet, Christopher could not shake the feeling that someone or something was watching him. With nervous glances over both his shoulders, he removed his flat tire and replaced it with a donut. As he stood up and wiped off his hands, he saw an eerie shadow emerging from the swamp. The shape was tall and appeared to be standing upright, even though something about it did not look quite human. As Christopher squinted into the darkness, the shape moved slowly towards him, walking on two legs. Seven or so feet off the ground, two red eyes, bright as lasers, pierced the night.

Christopher threw his tools in his car and jumped behind the steering wheel. Sweat now pooled along his brow as his foot punched the gas. His car sputtered forward, yet he knew he was not moving fast enough. Behind him, the creature’s enormous feet pounded the pavement, growing closer and closer. The creature lunged and latched onto the top of Christopher’s car. As Christopher swerved back and forth across the empty road, the creature slid down the back of the car, its claws scraping metal and etching scratches into the fender and sides. Within minutes, the creature lost his grip and tumbled to the ground, disappearing into the blackness of Scape Ore Swamp.

Christopher arrived home shaken. It took hours for his parents to console him, but, for fear of being mocked, he would not report the incident to the police—not until another family from Lee County reported strange marks on their car.

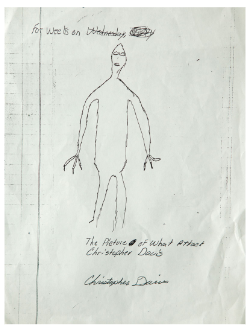

When he finally submitted a testimony to the police, Christopher would present a crude and simplistic drawing alongside his words. At the bottom of his drawing, Christopher Davis signed his name to designate the picture’s authenticity. From that moment, South Carolina’s first original cryptid—a creature, such as Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster, whose existence has never been proven—was born. The creature, first spotted on that warm June night, became the legendary Lizard Man.

***

I grew up in Columbia—South Carolina’s capital city, which has a population of around half a million. Until I moved away as an adult, South Carolina was the only home I ever knew. In the decades I lived there, I got to know the state well, taking trips to trendy towns and cities, beaches with uninterrupted shorelines, and trails in mountains whose blue-tinged aura is reflected in their name. As an adult, I even wrote a guidebook to the state’s natural areas for which I visited a state park directly adjacent to Bishopville, yet it didn’t crossed my mind to visit Bishopville itself—I simply thought of it as one of the many depressed rural towns in South Carolina I drove through on the way to somewhere else.

South Carolina is not unique with its wealth disparity problems wherein economic lines can be drawn between cities and rural places or between people of different races. In fact, Bishopville is so economically depressed that in 2017, its median household income was $21,000, which was nearly twice as low as the median income in the rest of South Carolina and $3,000 lower than Bishopville’s median income level twenty years earlier. Given these statistics, it's not surprising that 46% of Bishopville’s 3,000 residents live below the poverty line, and given the way wealth disparity is connected to race, it is not surprising that the 25% of the population that is white is significantly wealthier than the 70% of the population that is black. (The link between racial and economic disparity is especially poignant in Bishopville which originated as a cotton town.) All of this means that Bishopville is stuck in a cycle with no money for education, to entice industry, or to provide any means to life itself out of economic hardship. Yet, in the late 80s, when Christopher Davis started talking about an extraordinary, bizarre, terrifying monster he encountered late one night, the town began to buzz and many people felt a collective, palpable excitement, a sense of something new and unique in a town that had been fighting the same, complex issues for decades.

At the center of the commotion was Christopher Davis. Everyone wanted to talk to the person who had first seen Lizard Man. Christopher was in all the local papers, and soon, reporters from as far away as Australia were calling to talk about Lizard Man—some of them cryptid enthusiasts who believed wholeheartedly in Lizard Man, and others who wanted to laugh at the absurdity of the situation. Bishopville and South Carolina were in a frenzy—capitalizing on Christopher and Lizard Man any way they could. Immediately after Lizard Man’s sighting, Bishopville saw an influx of thousands of tourists clogging the I-95, many of which came to see Christopher as grand marshal of a festival parade. As the story gained momentum, Christopher drove as far as Myrtle Beach—a seaside resort city 2 hours from Bishopville—to sign t-shirts in a mall. For weeks, he was inundated with reporters, to whom he told his story more than 100 times a week.

Everyone watched as Lizard Man’s notoriety grew, and soon, locals began to come forward with their own terrifying encounters with the enormous scaly, bipedal monster Christopher described. George Plyler said that Lizard Man harassed his hogs and goats, killing several of them. Frank Mitchell was about to lift off from his grassy runway when a nine-foot tall creature with a loaf in his walk crossed in front of his small plane and made him abandon his flight. Dixie Rawson heard a terrible noise at night and woke up to see her car car riddled with scratches and deep holes that looked like they were punctured by enormous claws matching Davis’s Lizard Man drawing. An airman at Shaw Air Force Base, Kenneth Orr, claimed to have shot Lizard Man and he presented the sheriff with blood and scales. The scales turned out to be fish scales and Kenneth was charged with filing a false report and illegally carrying a gun. He recanted his story and signed a statement claiming, “I made the report just to keep the legend of Lizard Man alive.”

It seemed that everyone wanted to keep Lizard Man alive, and everyone wanted a piece of the action. A local radio station offered one million dollars to anyone who could bring the creature back alive, and residents and tourists flocked to Scape Ore Swamp with guns. Even local sheriff, Liston Truesdale, threw himself into the scandal, taking Lizard Man as seriously as any potential Bishopville threat. Truesdale did many interviews, encouraged witnesses with Lizard Man stories to come forward, and when someone reported strange, enormous 3-fingered tracks in the sand that matched Christopher Davis’s drawing, Truesdale personally drove out to the site and made casts that he planned to turn over to the F.B.I., until he was dissuaded from doing so.

Instead of giving them to the F.B.I., Truesdale eventually donated the casts to the South Carolina Cotton Museum, where they sit in a small glass case near the front of the rambling one-story brick building. Alongside the casts are a few other Lizard Man artifacts from the 1980s, including many different documents collected at the height of the frenzy and an assortment of colored t-shirts featuring dozens of different Lizard Man interpretations—a creepy goblin-esque Lizard Man wanders, hunched over, through an eerie, devastated landscape; a buff, hulk-like Lizard Man has lush, curly, shoulder-length hair; and a Barney look-a-like wears a t-shirt that identifies him as Lee’s Litter Lizard, encouraging citizens to pick up their trash.

When I visited the museum, after developing a Lizard Man fascianation, I saw no signage or interpretation of the collection, as one might expect to find in a museum, and instead had to read reviews and articles online to even figure out where many of the artifacts had come from. Even the question of why Lizard Man was part of the Cotton Museum’s collection was not answered at the museum, although when the collection was added, the director at the time, Janson Cox, did issue a statement to the press about why he chose to display the material: “Because no one else was dealing with it. Rather than seeing this material just gone, we’ve expanded our collecting policy.” It seemed that Lizard Man was a legend in every sense of the word—his story had been passed down by those who lived through the Lizard Man frenzy, he was too important not to be included in the town’s sole museum, and he had become completely wrapped up in the town’s collective lore.

As happens with lore and legend, there is no single, concrete narrative. Some cryptozoologists claim that Lizard Man is not a unique cryptid, but rather amidst darkness and terror, Christopher Davis misidentified the world's most famous cryptid, Bigfoot, as a giant lizard rather than a giant hairy ape. Others say that he is a modern manifestation of centuries-old regional folklore created by white slave owners attempting to scare slaves into submission with terrifying tales of monsters that thrived in the swampland bordereding plantations. Many speculate that Christopher ran off the road and invented a story to save himself from his parents' wrath, and because the town and the world responded so positively to him, Lizard Man grew and grew.

When I visited the Cotton Museum, the museum’s director told me that people visit from far and wide to see the Lizard Man exhibit, but even though they come for the cryptid, it provides a great opportunity to teach them about the history of cotton in South Carolina. Even though I had come to learn about Lizard Man, I ended up on a tour of antique farming equipment, tapestries, and a giant model of a Boll Weevil beside a tiny vial that contained an actual dead specimen of the beetle that once threatened South Carolina’s entire cotton crop. Lizard Man had been effective bait to get me to learn about what Bishopville was built upon.

Yet as I followed the director around the museum, I was surprised at how many parallels I saw between Lizard Man and Cotton. At first I had imagined that the Cotton Museum’s collection of Lizard Man was just another absurd element in an absurdist narrative about a mythic monster that lives in South Carolina’s swampland, yet in both, I saw difficult narratives being glossed over in favor of something more easily digestible. The Cotton Museum focused little on slavery and how its atrocities built South Carolina’s agricultural industry, just as Truesdale had focused on the simple, ridiculous threat of Lizard Man to Bishopville rather than the real issues the town faced.

I don’t think when Christopher Davis first told the world about Lizard Man, he expected the creature would be part of Bishopville more than than thirty years later, yet, it does not seem like Lizard Man is going anywhere. As years have passed, Lizard Man has become many different things to Bishopville: he has been a terrifying monster lurking in the shadows, he has been a celebrated hero who was able to bring tourism to town, and he has been a nuisance that has unleashed endless outside ridicule. Sometimes Lizard Man occupies all of these roles all at once, and sometimes, he is more one than the other. Yet, in all of these roles, Lizard Man has reflected Bishopville’s issues, and in doing so, has become both the town’s simultaneous friend and villain.

Lizard Man’s prominence in Bishopville ebbs and wanes with time. Sometimes, locals go years without hearing from or about him, and then, out of the blue, someone will pop up with a story or a grainy photo. Recently, a photo of a giant, muscled, comically rubbery Lizard Man walking across a field made its way across Twitter and a frenzied mockery of Lizard Man was ignited across media outlets, even as prominent as the Huffington Post and the Late Show with Stephen Colbert. To some, attention like this is embarrassing; others see the economic benefits.

Among the people that grew tired of the attention was Christopher Davis. At the height of his fame, it was rumoured that Christopher was scheduled to appear on the Oprah Winfrey Show but cancelled, and attempted to completely distance himself from the narrative. Eventually, Christopher even moved out of Bishopville to the nearby, larger city of Sumter where he largely disappeared from the public eye until, in his late thirties, he was murdered.

When Christopher Davis was shot and killed in 2009, at 37 years old, his photo and headlines linked him to the myth that he had actively distanced himself from for more than twenty years, using snappy headlines to quip about Lizard Man. In doing so, even in his death, Christopher Davis was outshined by Lizard Man.

Police: Murder victim Lizard Man witness

Famed Lizard Man witness killed

Suspect Charged In Lizard Man Witness' Death

In none of the articles is there any outrage or suprise that a young black man died of gun violence in South Carolina. Instead, the spectacle of Lizard Man was held up as more important than Christopher Davis or the actual issues that led to his death, such as poverty, racism, classism, drug abuse, and violence. With his death, it seemed as if everything that Lizard Man embodied and represented came full circle—real monsters, it seemed, would never get the attention that simple, easy, mythical monsters can garner. Even in articles about his death, we are not left thinking about Christopher Davis, we are instead left laughing at an enormous scaly green bipedal alligator with laser red eyes, wading through the algae-covered black creeks of South Carolina’s coastal plain.

Liesel Hamilton is a PhD candidate in nonfiction writing and holds an MFA from George Mason University. She is the author of Wild South Carolina (Hub City Press, 2016) and has been published in Catapult, The Normal School, and Audubon, among other publications. She has received fellowships from George Mason University and the Alan Cheuse International Writers Center.